It may not be immediately obvious that a link exists between the Ypres salient and the U Boat war of the First World War. However, Germany built submarine bases on the Flanders coast, only 30 miles from Ypres. Moreover, the 3rd Ypres (“Passchendaele”) campaign of 1917 had, as a strategic objective, the capture of these ports, such was the success of the German submarine campaign at that time.

Going back, in 1914, German forces took most of the Flanders coast. They realised quickly that the canal networks linking Ostend, Zeebrugge and Bruges could be accessed by small submarines: four boats were actually based there that winter.

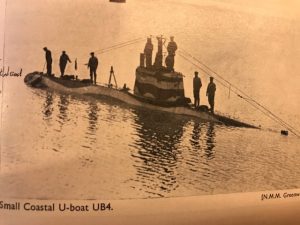

The point was that the boats had to be small. The U Boats building at the time (220 ft long, 950 tons) were too large for the canals. Consequently, Germany ordered a series of small coastal submarines (17 UB boats and 15 minelayer variants – UC boats), 90 ft long and 140 tons, which could be built quickly and which could be based in Flanders. A squadron was established formally in June 1915. Like the larger U Boats, these boats were numbered: UB1, UB2, UC1, UC2 and so on. Smaller numbers of these boats were sent throughout the war to the Mediterranean and to the Black Sea.

These boats were exceptionally fragile: 22 of the first order of 32 were lost in the war. One captain described his boat as being “like a sewing machine”. The remaining boats were phased out of front- line service in 1916.

A second series of boats (30 UB, 64 UC) was ordered in 1915; bigger boats (120 ft, 300 tons) and far more seaworthy. These boats were highly successful: estimates are that some 40% of the 11 million tons of shipping sunk by German submarines, related to the Flanders boats.

The peak year was 1917, the year of unrestricted submarine warfare: a political act which brought in the United States. A third series of coastal boats was ordered, 200 ft and 600 tons. 202 UB boats were ordered, of which 85 were completed by the war’s end and 113 UC minelaying boats were ordered, of which 15 were completed by the war’s end. The space in the Flanders canals was finite, so as these new boats became available, the second series was phased out of front-line service.

In 1918, a new series of 92 Flanders boats (UF) was ordered, but none were ready by the war’s end. These boats were 400 tons.

The numbers can be summarised as follows:

|

|

UB |

UC | UF | TOTAL |

|

|||||

|

Ordered |

Built | Lost | Ordered | Built | Lost | Ordered | Ordered | Built |

Lost |

|

| Series 1 1914 |

17 |

17 | 8 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 32 | 32 |

33 |

|

| Series 2 1915 |

30

|

30 | 21 | 64 | 64 | 41 | 94 | 94 |

62 |

|

| Series 3 1917 |

202 |

89 | 37 | 113 | 15 | – | 315 | 104 |

37 |

|

| UF 1918

|

92 |

92 | – |

– |

||||||

| TOTALS |

249 |

136 | 66 | 192 | 94 | 55 | 92 | 523 | 230 |

121 |

These numbers show three things: firstly, the sheer scale of the Flanders programme (523 boats ordered); secondly the unrealistic size of the 1917 and 1918 programmes and thirdly the very high loss rate: more than half of the boats built were sunk by Allied (predominantly British) forces, primarily in 1917 and 1918.

The numbers actually based in Flanders at a given point can also be shown:

- January 1916 14

- January 1917 28

- January 1918 41

- November 1918 26.

In addition to the UB/UC boats based in Flanders in November 1918, other UB/UC boats were deployed as follows:

- 21 in the Mediterranean

- 2 in the Black Sea

- 45 working up/training

- 15 decommissioned.

Were the Flanders boats a success?

“Success” would be defined in terms of Allied shipping sunk and the consequent impact on strategy.

The contemporary public has all but forgotten that there was a U Boat war in 1914-18. The Second World War U Boats sunk 13.8 million tons of shipping in 68 months. The First World War U Boats sunk 11.0 million tons in 50 months, so the monthly rate was actually higher in the First World War, with far fewer boats. Moreover, by 1918, the U Boats – just like their successors in the Second World War – were deploying as far afield as Long Island and Freetown.

The period 1917-18 nearly brought Britain to its knees: the level of shipping losses was unsustainable. However, a combination of the introduction of convoys and significant strengthening of British escorts (destroyers and sloops) had blunted the effect by the Spring of 1918.

The Flanders boats are said to have accounted for some 40% of the sinkings. Details of sinkings by individual boats are not comprehensive, but significant known sinkings by Flanders boats include:

- In 1917, the large British cruiser Ariadne, by UC65

- In 1918, the British Armed Merchant Cruiser Patia, by UC49

- In 1918, the 32,000 ton troopship Justicia, by UB64

- And two days before the Armistice, the British battleship Britannia, by UB50.

As to the strategic impact, the 1917 decision to initiate unrestricted submarine warfare brought in the United States, which meant that an Allied victory was inevitable.

Post script: St.George’s Day, 1918

One of the myths of the First World War is that the British raid on the Flanders bases on April 23 1918 blocked the canals and therefore, blocked the Flanders U Boats. This is not so.

Five obsolete cruisers were scuttled in the ports: 3 in the Bruges canal and 2 at Ostend. However, the ships were not placed correctly and the U Boats were able to get around them. A follow up at Ostend on May 9, by the cruiser Vindictive was unsuccessful, in spite of a heroic effort by the British landing parties.

Colin Kerr

October 2022